Over the last several decades, researchers have discovered a slew of genes involved in immune system processes that may have a role in Alzheimer’s disease.

Some of the leading possibilities are genes that govern the modest tiny immune cells known as microglia, which are now the subject of considerable study in developing novel Alzheimer’s treatments.

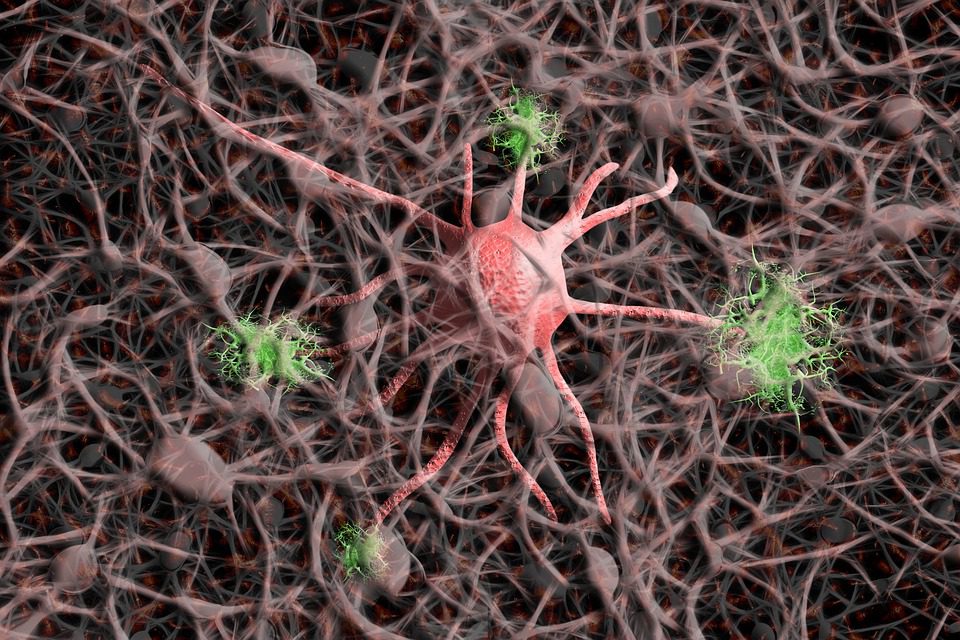

Microglia are amoeba-like cells that search the brain for damage and intruders. They aid in removing dead or damaged brain cells and physically consume invading germs.

We’d be in big trouble without them.

A protein called beta-amyloid gets cleaned away as molecular waste by microglia through our lymphatic system in a healthy brain.

But it does accumulate from time to time.

Specific gene mutations are one of the causes of this hazardous buildup. Another cause of decreased microglial function is traumatic brain damage.

Everyone agrees that in persons with Alzheimer’s, too much amyloid accumulates between brain cells and in the blood arteries that feed the brain with oxygen and nutrients.

When amyloid starts to block neuronal networks, it causes the buildup of another protein called ‘tau’ inside these brain cells.

The presence of tau activates microglia and other immune processes, producing inflammatory, immunological responses that many experts think eventually saps brain vibrancy in Alzheimer’s disease.

The Genetics Scene

So far, Alzheimer’s disease has been linked to roughly a dozen genes involved in the immunological and microglial activity. The first was CD33, which was discovered in 2008.

CD33 acts as a microglial on-off switch, activating the cells as part of an inflammatory cascade. Microglia generally identify as undesirable molecular patterns linked with pathogens and cellular injury.

This is how they know when to act – by devouring unknown infections and dead tissue.

Rudolph Tanzi, Harvard neuroscientist, thinks microglia interpret every hint of brain injury as infection and become hyperactive as a result.

“We kind of got it all going when it came to the genetics,” he says.

He says that most of our present human immune system originated hundreds of millions of years ago.

Our lifespans were far shorter back then than they are now, and the majority of individuals did not survive long enough to acquire dementia or the withering brain cells that accompany it.

So, he claims that our immune system believes that any defective brain tissue is caused by a microorganism rather than dementia.

Microglia respond vigorously, cleaning the region to prevent pathogen transmission.

“They say, ‘We better wipe out this part of the brain that’s infected, even if it’s not. They don’t know,” quips Tanzi. “That’s what causes neuroinflammation. And CD33 turns this response on. The microglia become killers, not just janitors.”

TREM2, discovered a few years after CD33, regulates microglial activation, restoring them to their original function as cellular housekeepers.

TREM2 researcher neurologist David Holtzman of Washington University in St. Louis agrees that there are microglia ready to scavenge when there is amyloid, tau, or dead brain cells.

“I think at first a lot of people thought these cells were reacting to Alzheimer’s pathology, and not necessarily a cause of the disease,” he says.

TREM2’s discovery, following on the heels of CD33, was pivotal, in part because it generates a protein present exclusively in microglia in the brain.

Genes are DNA sequences that encode proteins that operate our bodies and minds.

“Many of us [in the field] immediately said ‘Look, there’s now a risk factor that is only expressed in microglia. So it must be that innate immune cells are important in some way in the pathogenesis of the disease,” he adds.

Microglial activity, according to Holtzman, is a double-edged sword in the context of imminent dementia.

To preserve brain health, microglia clean out undesirable amyloid at first. However, after amyloid and tau have caused enough damage, the neuroinflammation caused by microglial activation does more harm than benefit.

Neurons perish in large numbers, resulting in dementia.

It seems that the most prevalent kind of dementia may be caused by a well-intentioned immune cell gone bad in many instances.

Leave a Reply