A team of researchers from the University of British Columbia’s faculty of medicine and BC Cancer Research Institute found a critical weakness in a fundamental enzyme that solid tumor cancer cells depend on to adapt and survive when their oxygen levels are low.

The findings were recently published in Science Advances, and they will certainly help scientists work on new treatment strategies to slow down the progress of solid cancer tumors, which represent most tumor types that form in the human body.

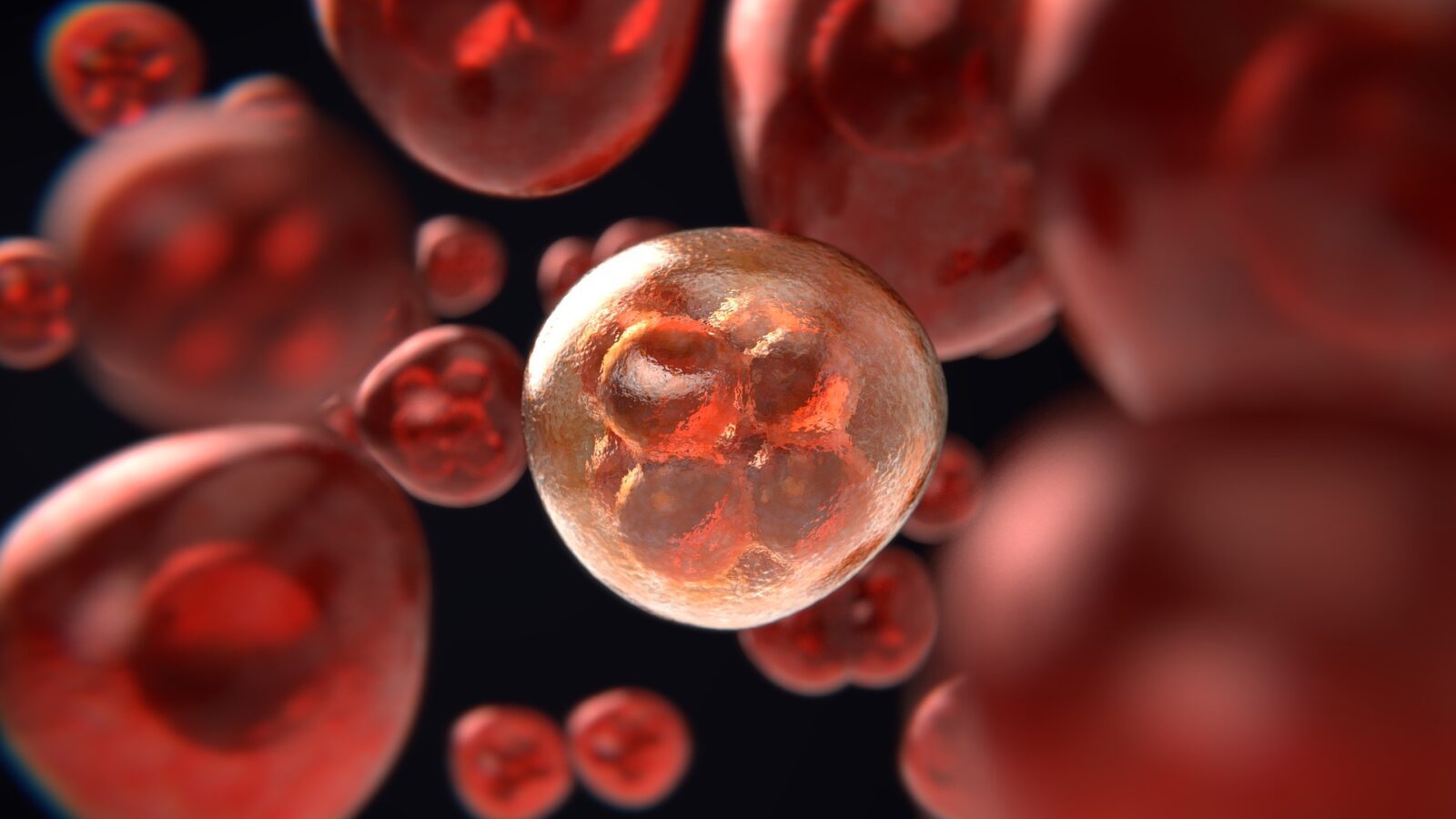

Solid tumors need a blood supply to intake oxygen and nutrients as a means of survival and growth.

As the tumors keep growing and spreading, the blood vessels can’t provide enough oxygen and nutrients to all parts of a tumor, leading to an area of low oxygen.

With time, the low-oxygen environment provokes a buildup of acid within the tumor cells.

To surpass that stress, cells produce enzymes that neutralize the acidic, hostile environment, helping them spread and become more aggressive, leading to a more dangerous tumor.

One of these enzymes is known as the Carbonic Anhydrase IX (CAIX).

Dr. Shoukat Dedhar, a professor in the UBC faculty of medicine’s department of biochemistry and molecular biology and distinguished scientist of BC Cancer, said:

“Cancer cells depend on the CAIX enzyme to survive, which ultimately makes it their ‘Achilles heel.’ By inhibiting its activity, we can effectively stop the cells from growing.”

Dr. Dedhar and his colleagues previously sampled a unique compound called SLC-0111, which, at the moment, is evaluated in clinical trials as a strong inhibitor to the enzymes that allow the cancers to grow.

As pre-clinical models of breast, pancreatic, and brain cancers have proven their effectiveness of the compound in limiting tumor growth and spread, it turned out that other cellular properties diminish its effectiveness.

The study is set to examine the cellular properties and how they impact other weaknesses of the CAIX enzyme. To do that, they will be using a high-tech instrument called the genome-wide synthetic lethal screen, which samples the genetics of a cancer cell and systematically deletes one gene at a time to figure out if a cancer cell can be eliminated by cutting off the CAIX enzyme with another particular gene.

Leave a Reply