According to a new research, the aging cycle may cause the Y chromosome to be destroyed, increasing the chance of cardiovascular failure as well as heart disease.

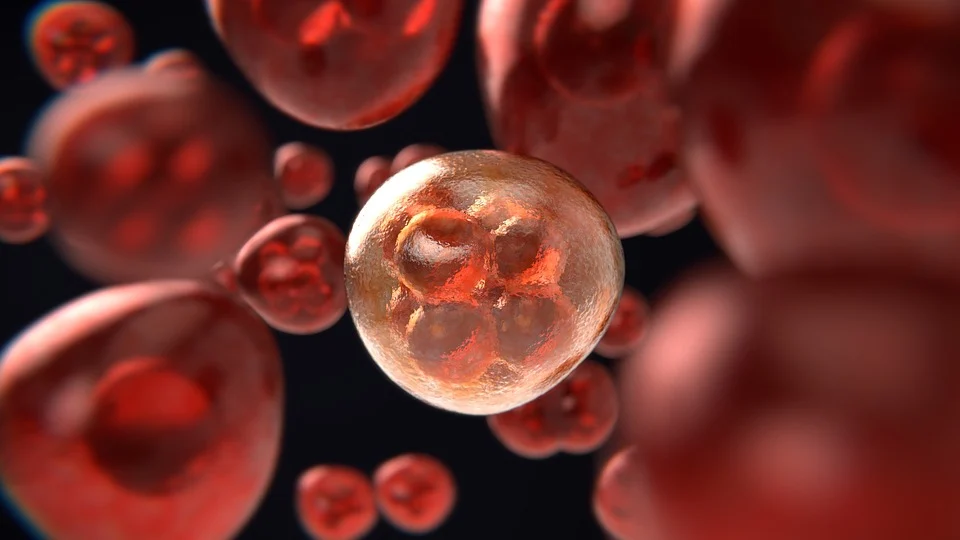

Men have one X & one Y chromosome, whereas most women carry two X chromosomes. In addition, the Y chromosomes of many men begin to disappear from the body’s cell types as they grow older.

Only in 2014, after decades of studying the phenomenon, did researchers discover that men who have lost their Y chromosomes tend to live shorter lives. There is now evidence that Y chromosomes are associated with cancer and Alzheimer’s disease, as well as other aging-related diseases. This loss has remained a mystery, though, since it’s not clear whether it’s only a byproduct of aging like creases or gray hair.

Y chromosome removal did not provide an acute impact on the younger mice, but they deteriorated over time and died at a younger age than mice with Y chromosomes intact. Fibrosis, an affliction in which scar tissue accumulates in the heart, was more common, as was a more rapid deterioration in heart performance as a result of the induced myocardial failure. A medication that prevents heart scarring was capable of restoring much of the mice’s lost cardiac function.

A massive collection based on genetic information from 500,000 people in the United Kingdom was evaluated by experts. More than 40 percent of white blood cells in males with Y-chromosome loss were shown to have an elevated risk of cardiac disease mortality, along with a two or threefold jump in the chance of death from congestive cardiac insufficiency or heart disease in comparison with men who had not shed their Y chromosomes. To put it another way, individuals who had suffered the largest loss of Y chromosomes had the highest chance of dying from heart disease.

Y chromosome decrease was found to cause scar tissue in the kidneys as well as lungs and even an increase in the frequency of cognitive decline in older mice.

Leave a Reply