Space flight is well-known for being very difficult for the human body, but a recent study has demonstrated exactly how difficult it is on red blood cells in particular.

Every second we are alive on this planet, our bodies generate and destroy 2 million of these cells.

According to recent research, astronauts lose 3 million red blood cells each second while in space, resulting in a loss of 54 percent more cells than humans on Earth.

Space anemia is a term used to describe low red blood cell counts in astronauts.

In a statement, study author Dr. Guy Trudel, a rehabilitation physician and researcher at The Ottawa Hospital and professor at the University of Ottawa, explained that since the earliest space trips, astronauts had experienced space anemia, but nobody knew why.

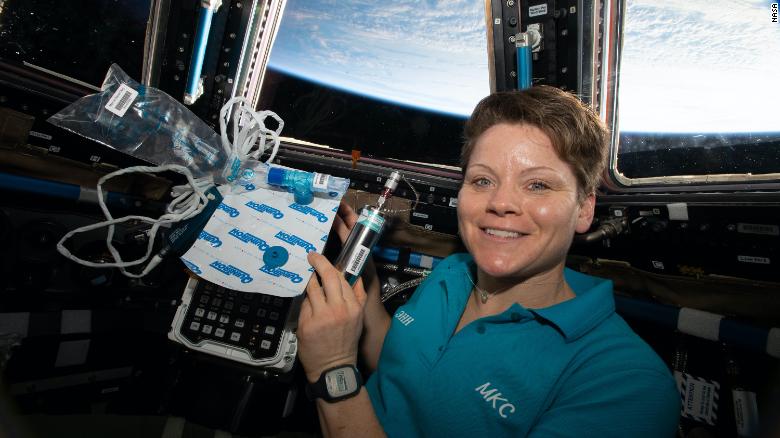

Before their six-month missions on the International Space Station, researchers collected samples of the astronauts’ breath and blood.

The astronauts, throughout their trips, collected a total of four samples.

The researchers also gathered the astronauts’ blood for up to a year after their mission was over.

According to the report, the 11 male and three women flights took place between 2015 and 2020.

Nature Medicine published the results on Friday, which were a surprise to no one.

Unexpected Discovery

In space, astronauts undergo a redistribution of physiological fluids toward the upper body due to the absence of gravitational pull on their bodies.

In turn, this leads to higher pressure on the brain and eyes, leading to cardiovascular problems and a 10 percent reduction in the amount of fluid present in their blood vessels.

Scientists assumed that space anemia was the body’s method of adjusting to the fluid change, which resulted in the loss of red blood cells to re-establish the proper balance.

They also believed that the red blood cell loss was temporary and would return after the astronauts had become used to the space environment after a 10-day stay in zero gravity.

Trudel and his colleagues came to a surprising conclusion: the space environment is the actual perpetrator in this situation.

In his statement, he said that the research demonstrates that upon arrival in space, more red blood cells are damaged, and this occurs for the whole length of the astronaut’s mission.

The study team devised methods for evaluating red blood cell damage, which included determining the levels of carbon monoxide identified in breath samples taken from the astronauts.

Each time one molecule of heme, or the red pigment that distinguishes red blood cells, is destroyed, it forms one carbon monoxide molecule.

Although the team was unable to directly assess the creation of red blood cells in the astronauts, they believe that the astronauts experienced an increase in the formation of red blood cells due to the higher destruction they encountered.

A failure to do so would have resulted in the astronauts suffering from the impacts and health difficulties linked with severe anemia while in space.

As Trudel points out:

“Thankfully, having fewer red blood cells in space isn’t a problem when your body is weightless,” Trudel said. “But when landing on Earth and potentially on other planets or moons, anemia affecting your energy, endurance and strength can threaten mission objectives. The effects of anemia are only felt once you land, and must deal with gravity again.”

Lingering Consequences

Following their return to Earth, five out of the thirteen astronauts were clinically anemic.

After landing, one of the astronauts did not get a blood sample as scheduled.

It was discovered via follow-up samples taken from the astronauts that space anemia is reversible since their red blood cell counts gradually restored to normal between three and four months following their return from the International Space Station.

However, tests taken a year after the astronauts returned to Earth revealed that the red blood cell loss rate had escalated by around 30% compared to what they had experienced before their space trip.

According to the researchers, this shows that long-duration space missions may cause structural alterations in red blood cells, which might have an effect on their function.

The findings are the first published data from the MARROW project, which evaluates the health of astronauts’ bone marrow and the creation of blood while they are orbiting the Earth.

These findings underscore the necessity of screening both astronauts and space tourists for health disorders that might be exacerbated by anemia and keeping a close eye on things while in orbit to avoid any complications during missions.

In recent research, Trudel and his colleagues discovered that longer space trips are associated with anemia.

For the time being, it is unclear how long the human body will be able to sustain an enhanced rate of both red blood cell loss and production at the same time.

In order to mitigate this danger, the researchers recommend that astronauts’ diets be modified in order to promote improved blood circulation.

In addition, the lessons learned from this study might be used to anemia patients on Earth, particularly those who suffer from the condition after an illness or extended bed rest.

However, although the exact cause of this kind of anemia is unclear, it may be related to what occurs in space.

According to Trudel:

“If we can figure out what’s causing this anemia, there is a chance that we will be able to cure or avoid it in astronauts as well as people here on Earth.”

Leave a Reply