Early results narrow atmosphere options, rule out a puffy “primary” envelope, and chart a clever path to isolate the planet’s true signal.

Key points

-

TRAPPIST-1 e sits in the star’s habitable zone—where surface liquid water is possible if an atmosphere exists. Webb’s first four transits with NIRSpec provide the most detailed look yet at this rocky world.

-

A light, primordial (H/He) atmosphere is very unlikely. Strong stellar activity from the red dwarf would have stripped such an envelope long ago. Researchers are testing scenarios for a denser secondary atmosphere—or none at all.

-

CO₂-dominated air (Venus- or Mars-like) appears unlikely, but multiple possibilities remain until more data arrive.

-

Innovative observing strategy: upcoming Webb visits time back-to-back transits of planet b (a likely bare rock) and planet e to separate stellar “noise” from the planetary signal. Fifteen additional observations are planned.

What Webb did—and why it matters

Webb uses transmission spectroscopy: when TRAPPIST-1 e passes in front of its star, a tiny fraction of starlight filters through any gases hugging the planet. Different molecules (H₂O, CO₂, CH₄, etc.) absorb at precise infrared wavelengths, leaving fingerprints in the spectrum that NIRSpec can read. Each additional transit stacks signal-to-noise, sharpening constraints on what is—and isn’t—there.

The team’s first four transits don’t show a telltale puffiness or strong molecular features from a hydrogen-helium atmosphere, which would have been the easiest to spot. Given TRAPPIST-1’s flares and energetic radiation, losing that early atmosphere is consistent with models for close-in M-dwarf planets. The open questions now revolve around secondary atmospheres (heavier gases outgassed from the interior or delivered by impacts) versus a bare rock.

A “world of (fewer) possibilities”

The data and modeling to date disfavor a CO₂-dominated sky like Venus (thick) or Mars (thin). That doesn’t end the habitability conversation, but it trims the family of plausible atmospheres and surface environments. Any surface water on a tidally locked TRAPPIST-1 e would likely require some greenhouse warming to stay stable—possibly as a global ocean or a dayside liquid patch ringed by nightside ice. The current spectra don’t exclude modest amounts of CO₂ that could help maintain such climates.

“TRAPPIST-1 is very different from our Sun, and so is its planetary system—that pushes our observing techniques and climate theories,” the team notes. More data are in the pipeline to probe these cases.

How the team will peel away the star’s “mask”

Red dwarfs are active; starspots and faculae imprint signals that can mimic or mute planetary features. To beat this, Webb will catch planet b and planet e back-to-back. Because TRAPPIST-1 b looks like a bare rock with no atmosphere, its spectrum during transit serves as a stellar baseline. Subtracting those star-only features from the subsequent TRAPPIST-1 e transit helps isolate anything that belongs to e itself—a powerful way to limit “stellar contamination.”

What we can (and can’t) say today

-

Detected: No definitive atmospheric detection yet. Primary (H/He) is unlikely.

-

Disfavored: A thick, CO₂-dominated atmosphere.

-

Still possible: A secondary atmosphere with heavier gases (e.g., N₂ with traces of CO₂, H₂O, etc.) at levels subtle enough to need many more transits; or no atmosphere. Upcoming data will tighten these bounds.

For context, related Webb results on neighboring TRAPPIST-1 worlds (e.g., TRAPPIST-1 d) also found no clear atmospheric signatures, underscoring how challenging it is for small planets around active M dwarfs to hold onto air. But each planet can differ; TRAPPIST-1 e remains the system’s premier habitable-zone target.

What’s next

-

15 more Webb observations of TRAPPIST-1 e are in progress, many using the paired b→e strategy. These will improve sensitivity to subtle spectral features and help test climate scenarios.

-

Parallel work continues to refine stellar activity models and noise correction, crucial for all small, cool-star exoplanets. Background explainers on Webb’s exoplanet program outline these challenges and goals.

See the data & imagery

-

Transmission spectrum (NIRSpec): NASA’s graphic comparing models with and without an atmosphere alongside current data points.

-

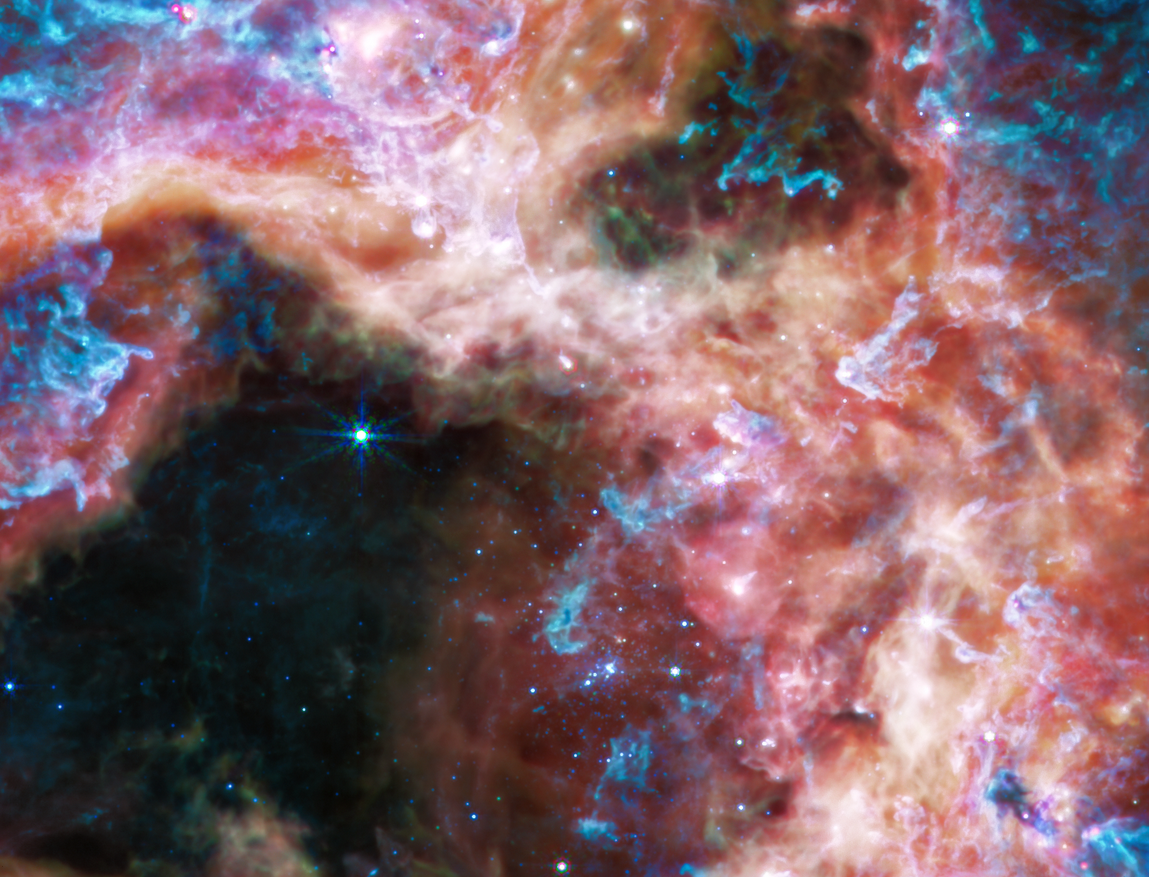

Artist’s concept: TRAPPIST-1 and its inner worlds as envisioned by the STScI team.

For additional coverage and context, see reports from Space.com and Universe Today summarizing the new Webb analyses and planned follow-ups.

Why TRAPPIST-1 e is special

At just ~40 light-years away and nearly Earth-sized, TRAPPIST-1 e sits squarely where surface water could exist under the right atmospheric blanket. It’s the archetype for what Webb—and future missions—aim to do: measure the climates of small, rocky exoplanets and evaluate whether any could be friendly to life as we know it. Each transit Webb captures brings us closer to a definitive answer.

Learn more

-

NASA release: NASA Webb Looks at Earth-Sized, Habitable-Zone Exoplanet TRAPPIST-1 e (with spectrum graphic and artist’s concept). NASA Science+2NASA Science+2

-

Background blog: Reconnaissance of Potentially Habitable Worlds with NASA’s Webb. NASA Science

-

Related STScI notes on nearby TRAPPIST-1 planets and atmospheres. stsci.edu

Credits: NASA/ESA/CSA/STScI; NIRSpec instrument team and collaborating scientists.

Leave a Reply